Do we sometimes decide that things look like Shakespeare because they are or do we try to make things look like Shakespeare because we can?

The Tudors created by that lover of historical English drama Michael Hirst (not the “atmospheric” musician by the way) had to have a little of the bard in it. Queen E One is in the freaking show after all.

Without going into a whole synopsis of the series, I’ll just say that it’s about King Henry VIII. Take three minutes for a refresher if you like.

In season three, Henry (played by love him or hate him Jonathan Rhys Meyers) fresh off lopping the head off the woman he created a religion to marry, finds a new girl, who dies and he is sad; being a king is hard.

Episode Five (Jeremy Podeswa, director)

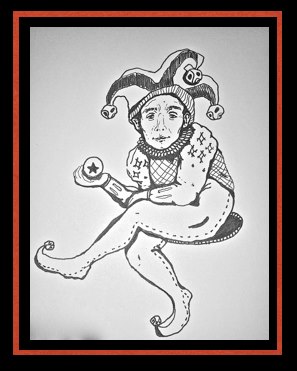

Henry secludes himself with Will Somers, the fool played by David Bradley (the one from Harry Potter not the country music superstar).

The fool’s first line: “I don’t think – are you mad – thinking is dangerous. But I’ll wink.”

Sound familiar?

When watching this episode I kept saying, ‘Lear!’

Wait a second, maybe it was me that was going crazy.

Here me out.

The ‘mad’ king Henry finds comfort with his fool after the death of Queen Jane (3 of 6). Henry rants about building a castle that will be the envy of all the world and draws on the floor; oh the vanity of kings. The fool mocks the king (naturally); a king all rightly fear. The fool says what all else want to (should?) say. The fool has a handful of scenes, but finds ways to deconstruct the entire series to that point in them.

Consider this exchange.

- Fool, “You find the perfect wife. She’s sweet, pliable, she even has good t*ts. On top of that she gives you the son you’ve always wanted and you let her die…And she’s not the only one, poor abandoned Katherine.”

- King, “Careful”

- Fool, “And that other one, who’s name escapes me…As her head escaped her. All lost! All lost!”

- Henry, “Go to hell.”

- Fool, “What? Go there? I thought I’d already arrived.”

The Tudors’ fool as well as Lear’s function on a different plane than the rest of the cast. The fools are not bound by the laws of decency censorship or tact. This dropping of curtains pushes both the play and show. Henry VIII and Lear are disrobed and their insecurities are played on. This is why we love us some fool. They say such cool things, and they GET AWAY WITH IT. To be a fool and not king would be oh so great thing (I just made that up).

Somers never returns in the series, and we are left with a very singular episode that is unlike all the others. The plot moves on in the other scenes, but it is the scenes with the fool that define the identity of Henry’s character. They move the show beyond plot, and embrace character. One thing I despise about many TV shows is there obsession with just chugging the plot along in a series of twists and turns that lead nowhere (sheesh 24 got stupid).

The success of the Tudors is the success of its characters. I was not prepared to like this show, but did as it went on. Season three, episode five turns the plot yes, but not in a gaudy, awkward way. It just moves the character(s).

I’ve always thought that there is a lot of Henry VIII in Lear. Both have three kids, both have issues with them, and both are erratic and grapple with madness and tyranny. I like the comparison, and this episode shows how the comparison can work if done right. Shakespeare, as all living at his time, must have been tempted to slide a little Henry into his plays. He was not far removed after all.

Bard Brawl c0-creator and bearded master of English Renaissance and TV hater Eric Jean says the only good season of the Tudors is season one featuring Cardinal Wolsey. Yeah, I get it, but no, you’re wrong Eric. Wolsey is alright, but the wives, Thomas Cromwell, that creepy Seymour brother and a ton of others not to mention the fool, make the show worth watching to the end.

Full disclosure: I’m a total sucker for historical dramas. I even watched that horrible Camelot series.

The final scene of episode five seals it for me. The fool sits on Henry’s throne wearing a crown maniacally laughing after Henry has just destroyed Cromwell’s reformation and rewritten the Lord’s prayer.

Very very nice.

Very Lear.